A Conversation With ... Everton Paul – Reggae Lane

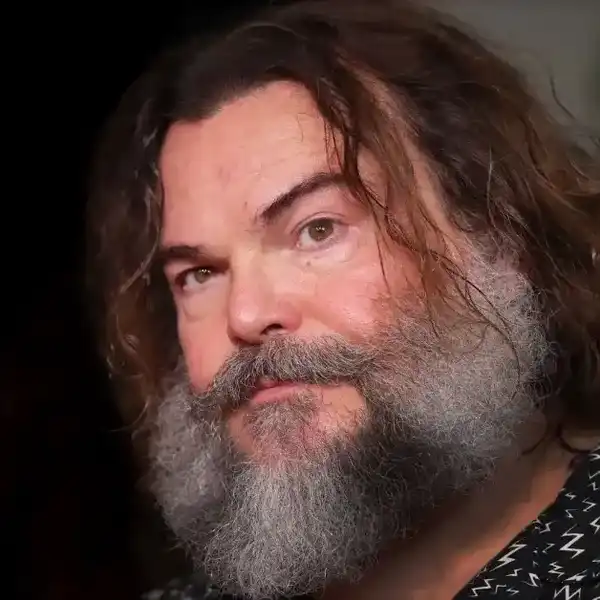

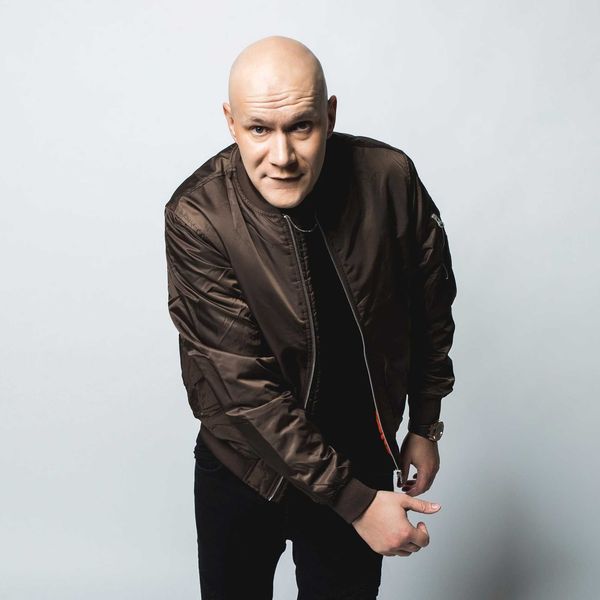

“Pablo” as he’s known throughout the music industry and to colleagues is by far my closest friend dating back to when we shared the bandstand between 1973-76 – before I departed for Los Angeles.

By Bill King

“Pablo” as he’s known throughout the music industry and to colleagues is by far my closest friend dating back to when we shared the bandstand between 1973-76 – before I departed for Los Angeles. For me, it was an introduction into a world of music I had a “buzz-on” for but no back history – ‘reggae’ and players much like the black Americans I shared a stage with most of the ‘60s. It was always about the “pocket” – that swirly beat, the roots of music, big laughs, and endless grooves. Paul’s place in Toronto’s music history is permanent. It’s that bridge between the Caribbean islands and mainland Canada that speaks to the evolution of an art form brought to world prominence by the late Bob Marley.

Bill King: Is there a date, a band or event that says – this was when reggae arrived in Canada?

Everton Paul: Reggae arrived in Toronto when Bob Marley made his debut at Massey Hall in 1974. Before that, the genre closest to reggae was ‘rocksteady.’ Jamaican music had been steadily evolving. It almost seemed like there was a search for the perfect groove, something genuinely Jamaican. It all started with the ‘bluebeat’ which was influenced by ‘jump blues’ which was music from America.

In those days Jamaican sailors working on cargo and cruise ships would bring back records from trips to the US - records by American musicians which in turn gave birth to the “sound system” and some fierce competition amongst the likes of Downbeat, Duke Reid, Tom The Great Sebastian and Count Pia. This led to DJs building sound systems, tube amps, and speaker boxes as each was aiming for maximum watts. Those competitions led to the next phase of evolution. DJs started to build recording studios and paying musicians to make music only available to a particular DJ who, in turn, gave them an edge if their audience widely accepted the tunes. I should point out that the various DJs had a devoted following.

‘Bluebeat’ led to ‘Ska’ which was the creation of The Skatalites. This group consisted of Tommy McCook, Roland Alfonso, “Dizzy” Johnny Moore, Lloyd Brivet, Jah Jerry, Lloyd Knibs, and my good friend Jackie Mittoo. Ska rhythm slowed down and gave birth to ‘Rocksteady.’ In both styles, the beat landed on two and four whereas reggae, the beat landed on the three-beat and was considerably slower with a hypnotic influence. One, two, beat four.

B.K: Growing up in Kingston, Jamaica - what music was a young drummer playing in the ‘60s?

E.P: The ‘60s in Jamaica was a time when music was going in many directions. There was ska, jump up, early R&B - the introduction of rocksteady and continued influence of American music. Through that, young drummers had to familiarize themselves with all genres because the bands of that era would play a variety of music. I was a great fan of Latin music, influenced by a conga player by the name of Noel Seals, a neighbour of mine. He would listen to Cuban stations, and when the name of a conga player was mentioned, he would comment he knew that individual - of course, Noel spoke perfect Spanish and would occasionally make trips to Cuba. Because of his influence, my first instrument was the conga and bongos. My tools were made from paint cans until my brother-in-law sent me a drum from Canada. Before that, I had the opportunity to play Noel’s congas, interrupting his practice time.

B.K: When did you get your first set of drums, and what was the circumstance?

E.P: I got my first set of drums - not my own but was offered a drum set. The opportunity came through the owner-manager of The Comets, a new group that was led by Lyn Taitt. The road manager was making a trip to Miami to purchase new instruments for the band, and the musicians had the opportunity to order whatever brand of the instrument they played. My choice of drums was a set of “Rogers.” When the equipment arrived in Jamaica, the drums were delivered to my house, and that made it possible for me to practice. With the band I had played in before The Cavaliers, management kept all the instruments at their storage facility.

B.K: Were other teens acutely aware of the music coiling around them?

E.P: You have to understand, in Jamaica, the social-economic divide created a situation where some teens were very aware, and then there were the teens who, because of their parent’s station in life, would be prohibited from being involved in the so-called “low-class” environment. When you think about it, the music of the ghetto was in the air, and one would have to be deaf to avoid it. The “uptown folks”, as they would refer to themselves, would go to clubs - dance and party to the same music performed by Byron Lee, Carlos Malcolm, Kes Chin and The Presidents and of course those bands only appeared at certain spots in and amongst the ghetto folks unable to pay the cover charge. Much of the music played on the sound systems was created by “ghetto people” - youth considered “bad boys” who’d eventually end up at Alpha Boys School, a trade school - a form of punishment. Not all the boys that ended up there were unruly, some were disadvantaged, or dealt a bad hand in their early childhood.

B.K: Did your parents own a Hi-Fi?

E.P: Growing up - radio as we know it today have multiple bandwidths on AM and FM and numerous stations. Back then, there was a radio system known as Radio Fusion (“redy fusion”). It was a one-channel radio operating on a cable system. If you had a radio and didn’t have the cable, it would be of no use. It was one channel with regularly scheduled programs, a wooden speaker box with one control knob, three settings, and volume off and on. You didn’t buy this unit; it was a rental. If you didn’t pay, there goes the box.

The first radio station was RJR - Radio Jamaica and Radio Fusion. Eventually, my parents bought an RCA Victor with multiple channel options. With a decent antenna, we could get WINZ, an American station around 10 or 11 PM, or a station from Havana. My friend Noel had a short-wave radio and could get Cuba during the daytime. Then came (JBC) Jamaica Broadcasting Corporation.

Both local stations would play popular music - mainly American groups - occasionally a Jamaican group. Over time more local artists found their music played on air. Oldest brother Bunny bought a small hi-fi system with a record player attached. He bought recordings of U.S. groups: Clyde McPhatter, Fats Domino, Sam Cooke, Ben E King, The Platters, and more. My source was local music and readily available on a Friday and Saturday night from the two dance halls just a few blocks up the road from my house. At the Centre and Blue Ribbon, the DJs battled it out. These were open-air venues. The sound would rip through the night and believe me; there was no calling the police to make a noise complaint because they couldn’t give a damn. Those uptown people living up the hill had no option but to live with it.

B.K: What played on the device?

E.P: In those days, the 78 RPM was the standard format and made from Bakelite. The advantage to Bakelite, made from a ‘heavy’ compound, was that it would not warp easily. The disadvantage was if you accidentally dropped, you may end up having to play a song with a great deal of it missing. For DJs, it was a challenge transporting the discs to the various dance halls. The hi-fi had three speeds: 78, 45, and 33 1/3. We owned records that played at all speeds.

Fridays and Saturdays the hi-fi would get a workout, especially leisure evenings. Friday in our house, a new record would get played over and over, and quite often, my mother or aunt would shout, “stop, you’re going wear it out.” Eventually, they switched from Bakelite to vinyl, but Jamaica being a tropical climate, you had to be very careful how you stored those records - never near windows and away from the sun’s ray otherwise the tonearm would dance up and down violently and skip whole sections of a song. Fun times, however.

B.K: Kingston can be a tough place to spend one’s youth. How did you avoid conflict and turf battles?

Fortunately, I lived in an area that was not wholly within the “turf war zones,” and my friends were from middle-class families. Having an interest in music kept me focused. Back then, the old folks used to say, “the Devil finds work for idle hands.” I can remember on sweltering nights my father would sleep outside in the backyard on a cot, a travelling bed used mostly by the military, and the back door to the house was left unlocked. Those times were so safe that when I was out playing, there was no need to carry a key to the house, the back door left unlocked for me, and there was never a “break and enter.” Of course, it wouldn’t have been called B and E; it would have been called “Enter.”

When I left for Canada, the house didn’t have “burglar bars.” My first visit back after being away for about five years, I was shocked to see every window and door outfitted with patterned steel grills, even the front veranda enclosed. A definite sign that the turf was changing. Things have now changed for the worse as most of the regular families have moved up or away. The guns are now everywhere.

When I was a youth, scores were settled by fistfights; the occasional knife was drawn and, most times, never used as the culprit was usually a coward. The guy with the blade wouldn’t use it, and the other guy was not so sure so things would end with a “next time I will fix you.” And yes, Kingston is a tough place if you are in the wrong place, especially if you are not regular or live in the neighbourhood.

B.K: What’s the back story on you and legendary Jamaican artist Jackie Mittoo?

E.P: The story behind Jackie and me was sheer coincidence. It seemed as if I started a trend in musicians coming to Toronto. Bass player Lloyd Spence who played with the Cavaliers and then Lyn Taitt and the Comets, migrated to Canada about a year after I did as did Honeyboy Martin, Jackie Mittoo, Lord Tanamo and number of other musicians. Jackie would come to the different venues we were playing and eventually asked me to do gigs with him.

We made a three-state trip in the U.S. I was hired by him to work on his Wishbone album, which was a huge production with strings and lots of horns, two drummers - Joe Isaacs from Jamaica the other drummer but his timing was not very good when playing “drum-fills” - so my job was to hold it together. I played weekly gigs at the Bristol Place Hotel out by the airport with Jackie, Terry Logan, and Lord Tanamo. I also did a lot of reggae shows, including the one at the Masonic Temple at Yonge and Davenport, where I first met you.

B.K: If you were to name the founding members of the Toronto reggae scene, who would they be?

E.P: Well, as I said earlier, reggae didn’t come to Toronto till Bob Marley played Massey Hall. I would say Jackie Mittoo was one of the pioneers of reggae. Stranger Cole, Leroy Sibbles, The Satallites with JoJo Bennett, and Fergus Hambleton; they were regulars at the BamBoo. There was also a group called Chalawa with John Forbes and Alex King “Teach.” I did one show with them in Montreal when we opened for Peter Tosh; now everybody is doing reggae.

B.K: What was Harry’s after-hours place and what was its importance to the local West Indian scene?

E.P: Harry’s was unique and a special place. First of all, Harry was operating his after-hours spot right behind 52 police division, the police station on Eglinton by the Allen Expressway. There was liquor, gambling, music, food, and weed. I think every Jamaican musician in Toronto would hang at Harry’s after hours on different nights, some for the music of which Harry had quite the collection and a fantastic McIntosh system with some “big ass” speakers. The food was always fresh and tasty - the “weed” - the best from the backyard, and the bar were always stocked - a source of income for him.

As close as the police station was, there was never a need to feel uncomfortable, and everyone respected the neighbourhood. It was “up and up” when inside where the action was, and most of all, Harry was a gentleman.

Harry was quite knowledgeable about music and musicians, which was his passion. He never played an instrument though one may get the impression that he did from his conversations and music authority. I remember when I went on a short tour in the U.S. with Jackie, Harry was there. He was quite fond of Jackie, as was everyone else.

B.K: Reggae Lane? How long was this in the works, and what is the significance of this for Torontonians?

E.P: 'Reggae Lane' was something that Jay Douglas had fought hard to establish. He wanted to make sure that he and all the other players in reggae got the recognition they deserved. The stretch of Eglinton Avenue, where “Reggae Lane” is situated where a large part of the Jamaican diaspora has conducted business, dined, selling food, clothing, hair salons, barbershops, and of course music shops. Jay worked very hard lobbying the city counsellors from the neighbourhood to get “Reggae Lane” recognized. The significance of it may be lost on most Torontonians as it’s not an area that they may frequent, but I think it instills a great sense of pride for people who live, work, and conduct business there. There are plaque and extensive murals erected, which list the names of many reggae artists who have been a part of the scene, including the Cougars, and it’s all thanks to Jay. A job well done.